Snakes, a diverse group of limbless reptiles, have captured the fascination of humans for centuries. Their sleek bodies, unique movement, and often venomous nature make them both intriguing and feared. To truly appreciate these enigmatic creatures, we must delve into the intricacies of their Anatomy of a Snake and Its Function that allow snakes to thrive in their diverse environments.

Introduction to Snake Anatomy

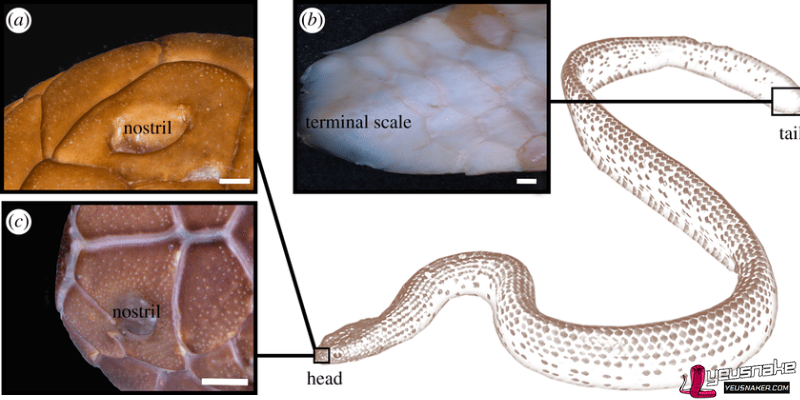

Before exploring the various parts of a snake’s body and their functions, it is essential to understand some general characteristics of snake anatomy. Snakes belong to the suborder Serpentes and are characterized by elongated bodies covered in scales. They lack limbs, eyelids, and external ears, but they possess a highly specialized skull structure and unique adaptations for locomotion and feeding.

Snakes come in various shapes and sizes, with some reaching several meters in length, while others remain as small as a few centimeters. Their diversity extends to their habitats, with snakes inhabiting deserts, rainforests, grasslands, and even aquatic environments.

The Skin and Scales

A snake’s skin is a remarkable feature that serves multiple functions beyond simply providing a physical barrier. It is composed of scales, which are modified epidermal structures made of keratin. The scales overlap and interlock, providing protective armor for the snake’s body. They also help reduce water loss, making snakes well-adapted to arid environments.

One of the most fascinating aspects of snake skin is the process of shedding, known as ecdysis or molting. Snakes periodically shed their old skin to accommodate their growth. This process also helps them remove parasites and any injuries to the skin. Prior to shedding, a snake’s eyes become cloudy or “blue,” a sign that the process is about to begin. The skin is shed in one complete piece, leaving behind a remarkably detailed replica of the snake’s body.

Skull Structure and Jaw Mobility

The skull of a snake is highly specialized to suit its unique feeding habits. Snakes are carnivorous predators, and their skulls are designed to consume prey much larger than their head’s size. The lower jaw of a snake is not fused, and both halves can move independently. This unique adaptation, known as cranial kinesis, enables the snake to swallow large prey items by opening its mouth to an incredible extent.

Additionally, snakes possess a specialized jaw joint called the quadrate bone, which allows them to “walk” their jaws over prey during swallowing. This mechanism, combined with the ability to dislocate their jaws, allows snakes to consume prey much larger than their own head, making them efficient predators.

Locomotion and Muscular System

The absence of limbs does not hinder snakes from moving with surprising agility and speed. Snakes utilize their muscular system to perform a variety of locomotion styles, including serpentine (side-to-side), rectilinear (straight-line), concertina (constriction), and sidewinding (used in sandy environments).

The muscles responsible for snake locomotion are arranged in a series of diagonal bands, called myomeres, along the snake’s body. These muscles work in an alternating manner to propel the snake forward. By anchoring their belly scales to the ground and pushing against it, snakes generate the necessary friction to move.

Some snake species have specialized adaptations for particular habitats. For example, tree-dwelling snakes have prehensile tails that aid in climbing, while burrowing species may have powerful muscles for digging.

Sensory Organs

Despite the absence of external ears, snakes have excellent hearing capabilities. They detect sound waves through their lower jaw, which is connected to their inner ear. When sound waves reach the snake’s jaw, they vibrate the quadrate bone, transmitting the vibrations to the inner ear.

Vision varies among snake species, with some having excellent eyesight and others relying on other sensory organs. For instance, pit vipers possess heat-sensing pits located between their eyes and nostrils, which enable them to detect infrared radiation emitted by warm-blooded prey.

Snakes also possess a highly developed sense of smell through their Jacobson’s organ, located in the roof of their mouths. This organ detects and analyzes chemical cues in the environment, aiding in locating prey and potential mates.

Venomous Snake Anatomy

Venomous snakes possess additional anatomical structures related to their venom delivery. The venom is produced in modified salivary glands located behind the snake’s eyes. It is then delivered through specialized hollow fangs located in the upper jaw. When the snake strikes its prey, venom is injected through these fangs, rapidly immobilizing or killing the victim.

Some venomous snakes have fixed fangs, while others possess retractable fangs that fold against the roof of the mouth when not in use. The composition of snake venom varies widely, with different species targeting different physiological systems in their prey.

Digestive System

The digestive system of snakes is highly specialized to accommodate their carnivorous diet. Once a snake has captured its prey, it uses its powerful jaws and teeth to consume it whole or in large pieces. The prey is then transported to the snake’s stomach, which has highly acidic juices to aid in the breakdown of proteins and other nutrients.

Snakes have elongated intestines to maximize nutrient absorption, as well as specialized organs like the gallbladder and pancreas, which aid in the digestion of fats and carbohydrates, respectively. However, due to the lack of limbs, snakes cannot chew their food, so they rely on powerful muscles and digestive enzymes to break down the prey.

Reproductive System

Snake reproduction varies among species, with some being oviparous (laying eggs), others being ovoviviparous (retaining eggs internally and giving birth to live young), and a few being viviparous (nourishing the embryos internally and giving live birth).

Males have a pair of reproductive organs called hemipenes, located near the base of the tail. During mating, one of the hemipenes is inserted into the female’s cloaca, allowing for sperm transfer. Female snakes can store sperm for extended periods, using it to fertilize multiple clutches of eggs.

Conclusion

The anatomy of snakes is a testament to the marvels of evolution and adaptation. From their scale-covered bodies and specialized jaws to their unique locomotion and sensory systems, every aspect of their anatomy serves a specific function that allows them to thrive in diverse environments. Despite the fear and mystery surrounding them, understanding the anatomy of snakes sheds light on the intricacies of the natural world and highlights the beauty of these remarkable reptiles. As we continue to explore and appreciate the wonder of nature, may we strive to conserve and protect these enigmatic creatures for future generations to marvel at and learn from.